Most people think generic drugs are cheap because they’re generic. But the truth? Insurers aren’t saving money just because generics exist-they’re saving because they’re bulk buying and running competitive tendering processes that force manufacturers to slash prices. It’s not magic. It’s math. And it’s happening behind the scenes of your prescription co-pay.

Back in 1984, the Hatch-Waxman Act opened the door for generic drug approvals in the U.S. Overnight, companies could copy brand-name drugs without repeating expensive clinical trials. But it wasn’t until insurers and pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) started using their buying power that prices really dropped. Today, generics make up over 90% of all prescriptions filled in the U.S., yet they account for just 17% of total drug spending. That’s $445 billion saved in 2023 alone, according to the Association for Accessible Medicines. Most of that savings comes from how insurers buy.

How Tendering Works: The Bidding Game Behind Your Prescription

Imagine you’re buying toilet paper for a hospital with 10,000 beds. You don’t just pick the first brand you see. You send out a request to five manufacturers: "Give me your lowest price for 1 million rolls, delivered monthly for two years." The lowest bidder wins. That’s tendering-and it’s how insurers buy generic drugs.

Insurers don’t buy one drug at a time. They group drugs by therapeutic class-like blood pressure meds, diabetes pills, or cholesterol reducers-and invite multiple generic makers to bid. The contract usually lasts one to three years. In exchange for guaranteed volume, manufacturers agree to prices that can be 80-90% lower than the original brand. A first generic for a drug like bortezomib (used for multiple myeloma) saved over $1 billion in its first year after approval, according to the FDA.

But here’s the catch: not all generics are created equal in price. Some have only one or two manufacturers. Others have five or more. Insurers use software to flag the high-cost generics-those with few competitors-and push for substitutions. If your doctor prescribes a $120 generic version of a drug, but there’s a clinically identical version for $12, insurers will swap it automatically. You won’t notice. Your co-pay stays the same. But the insurer saves $108 per prescription.

Why Your Co-Pay Doesn’t Reflect the Real Savings

You might think, "If generics are so cheap, why am I paying $25 for my blood pressure pill?" The answer lies in how PBMs structure formularies. Most insurance plans put generics on tier 1 or 2, meaning lower co-pays. But here’s the twist: many Medicare Part D plans still put generics on higher tiers with $25-$60 co-pays, even though the actual cost to the insurer is under $5. Why? Because PBMs profit from the gap between what they pay the pharmacy and what they charge the insurer.

This is called "spread pricing." PBMs like OptumRx, Caremark, and Express Scripts (which together manage benefits for 280 million Americans) negotiate a price with the pharmacy-say $8 for a 30-day supply of lisinopril. But they bill the insurer $30. The $22 difference? That’s their cut. And they have no obligation to tell you or your employer. A 2022 JAMA Network Open study found that plan sponsors often don’t even know which generics are driving up costs because pricing is hidden.

That’s why some people pay $87 out-of-pocket through insurance for a generic drug, then walk into a Cost Plus Drug Company and pay $4.99. Or use GoodRx and save $32 a month. Cash payments for generics have jumped to 97% of all cash prescriptions-even though cash makes up only 4% of total prescriptions. People are figuring out that insurance isn’t always helping them save.

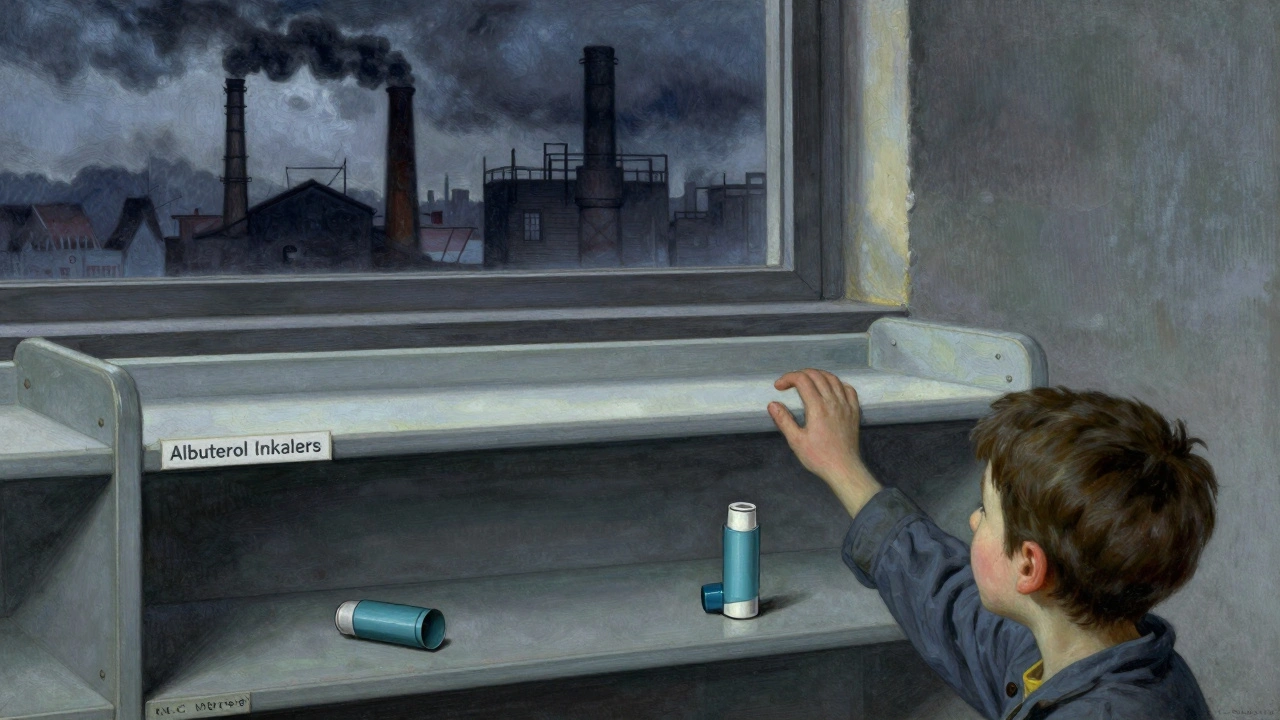

The Hidden Cost: When Price Cuts Cause Shortages

There’s a dark side to this savings game. When insurers demand prices so low that manufacturers can’t cover production costs, they walk away. That’s what happened with albuterol inhalers in 2020. The price dropped below $1 per unit. Manufacturers shut down production. By the time shortages hit, 87% of U.S. hospitals couldn’t get the drug. Patients were forced to use more expensive alternatives-or go without.

It’s not just albuterol. The FDA’s Drug Competition Action Plan found that just three manufacturers produce 80% of generics in certain therapeutic classes. That’s not competition-it’s a cartel waiting to happen. When there’s no real competition, tendering doesn’t work. Prices don’t drop. They just stay stuck.

And when manufacturers leave, the few left behind raise prices. It’s a cycle: too much pressure → shortages → less supply → higher prices. The system is designed to save money, but it’s fragile.

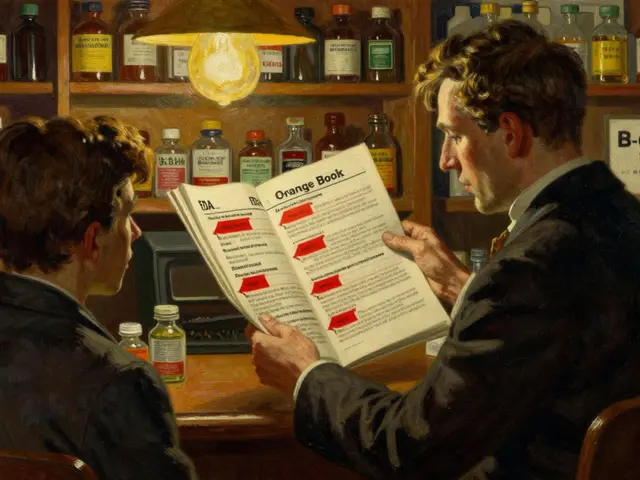

What’s Changing: Transparency, Direct-to-Consumer, and Policy Shifts

More people are bypassing the PBM system entirely. Mark Cuban’s Cost Plus Drug Company, which started with one location in 2022, now has 35 across 12 states. They charge 15% over wholesale cost plus a $3 flat fee. No spreads. No rebates. No hidden fees. A 2023 NIH study found these models save patients 75-91% compared to retail pharmacies. One Blueberry Pharmacy user on Trustpilot said: "My blood pressure medication costs exactly $15/month with no insurance surprises."

States are stepping in too. California’s Senate Bill 17 (2017) forced PBMs to disclose any spread pricing over 5%. Other states are following. In January 2024, Medicare Part D got new rules requiring more pricing transparency. The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 didn’t fix the PBM problem-but it did cap insulin at $35 for Medicare patients. That’s a start.

Employers are also waking up. Navitus Health Solutions, a PBM that works directly with employers, reported 22% lower generic drug costs in 2023 than traditional PBMs. How? They cut out the middleman. They pay manufacturers directly. They don’t take a spread. They don’t hide prices. They just negotiate volume discounts and pass the savings along.

What You Can Do: Save Money Without Waiting for Insurance to Fix It

You don’t have to wait for your insurer to change its system. Here’s how to save right now:

- Check GoodRx or SingleCare before filling any generic prescription. Often, the cash price is lower than your insurance co-pay.

- Ask your pharmacist: "Is there a cheaper generic version?" Sometimes, switching brands cuts the cost by 80%.

- If you’re on Medicare, compare Part D plans every year. The cheapest plan isn’t always the one with the lowest premium.

- Consider direct-to-consumer pharmacies like Cost Plus Drug Company or Blueberry Pharmacy if you take regular generics.

- Call your insurer and ask: "Do you use spread pricing? Can you show me the actual cost of my generic drugs?" If they can’t answer, it’s time to switch.

Insurers save money on generics by playing a high-stakes bidding game. But you don’t have to play by their rules. The savings are real. The system is broken. And you have options.

Why are some generic drugs so expensive even though they’re generic?

Some generics cost more because they have few manufacturers-sometimes just one or two. When competition is low, prices don’t drop. Insurers call these "high-cost generics," and they’re often the result of manufacturing consolidation or patent tricks. A drug like metformin might cost $5, but a less common generic like lacosamide could still cost $100 if only one company makes it.

Do PBMs really make money off the difference between what they pay and what insurers pay?

Yes. This is called spread pricing. PBMs negotiate a price with pharmacies-say $10 for a drug-then bill the insurer $40. The $30 difference is their profit. Many insurers don’t know this is happening because contracts are opaque. California and a few other states now require PBMs to disclose spreads over 5%.

Can I get the same generic drug for less by paying cash?

Often, yes. A 2023 NIH study found cash prices at direct-to-consumer pharmacies were 75-91% lower than retail prices. For expensive generics, that’s $231 saved per prescription. For common ones, it’s $19. If your insurance co-pay is over $15, it’s worth checking GoodRx or Cost Plus Drug Company.

Why do insurance plans put generics on higher tiers with higher co-pays?

Some plans do this because PBMs push them to. If a generic drug has a high spread, the PBM benefits more if you pay a higher co-pay. The insurer gets paid back more, but you pay more. It’s a perverse incentive. About 78% of Medicare Part D plans still put generics on higher tiers, even though they’re cheaper to buy.

How do I know if my insurer is using bulk buying and tendering effectively?

Ask for a list of your top five generic drugs and their actual acquisition cost. If your insurer can’t provide it, they’re likely not transparent. Effective tendering means they’re constantly comparing prices, switching manufacturers, and eliminating high-cost generics. If your co-pay hasn’t dropped in three years despite new generics entering the market, they’re probably not doing their job.

Written by Martha Elena

I'm a pharmaceutical research writer focused on drug safety and pharmacology. I support formulary and pharmacovigilance teams with literature reviews and real‑world evidence analyses. In my off-hours, I write evidence-based articles on medication use, disease management, and dietary supplements. My goal is to turn complex research into clear, practical insights for everyday readers.

All posts: Martha Elena