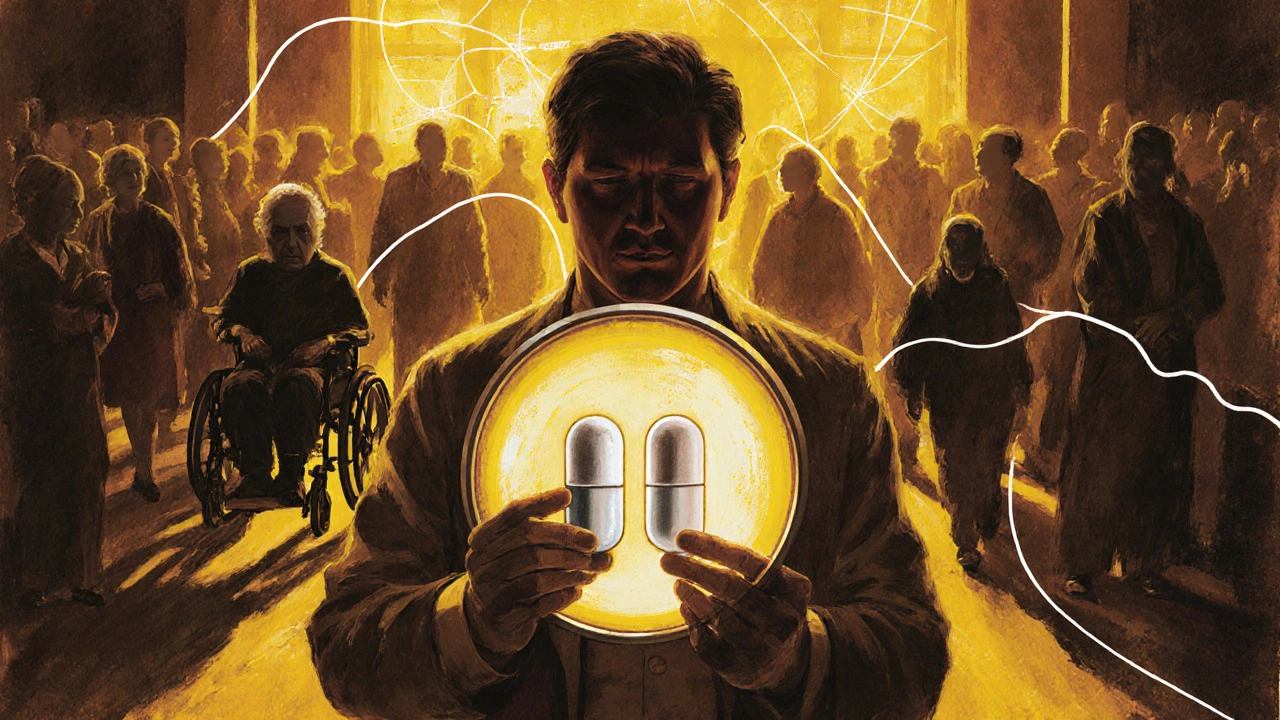

When a new generic drug hits the market, how do regulators know it works just like the brand-name version? It’s not enough to say the ingredients are the same. The real question is: does your body absorb and process it the same way? That’s where population pharmacokinetics comes in - a powerful, data-driven method now used by the FDA, EMA, and major drug companies to prove drug equivalence without relying on traditional, invasive studies.

Why traditional bioequivalence studies fall short

For decades, proving a generic drug was equivalent to the brand version meant running a crossover study with 24 to 48 healthy volunteers. Each person would take both versions, blood samples would be drawn every 15 to 30 minutes for hours, and researchers would compare the average drug levels in the bloodstream - specifically the area under the curve (AUC) and peak concentration (Cmax). If the ratio fell between 80% and 125%, the drugs were deemed bioequivalent. But here’s the problem: healthy young adults don’t represent most patients. People with kidney disease, older adults, children, or those on multiple medications often respond differently to drugs. Traditional studies rarely include them. And when they do, it’s expensive, ethically tricky, and logistically hard to get enough data. Take a drug like warfarin, used to prevent blood clots. A 10% difference in how it’s absorbed can mean the difference between a stroke and a dangerous bleed. Testing this in frail elderly patients with frequent blood draws isn’t practical - or safe. So how do you prove equivalence in real-world populations? Enter population pharmacokinetics.What is population pharmacokinetics (PopPK)?

Population pharmacokinetics, or PopPK, is a statistical modeling approach that looks at drug concentration data from many people - often hundreds - collected during routine care. Instead of requiring 10 blood draws per person, PopPK works with just 2 to 4 samples per patient, gathered at random times during normal treatment. It doesn’t assume everyone responds the same. Instead, it asks: Why do responses vary? Is it because of weight? Age? Kidney function? Other drugs they’re taking? PopPK builds a model that finds patterns across this messy, real-world data. It separates variability into two parts: differences between people (between-subject variability) and random noise or measurement error (residual unexplained variability). The math behind it is complex - nonlinear mixed-effects modeling - but the goal is simple: predict how a drug behaves in any patient, given their characteristics. This lets regulators and drug makers answer a much more useful question than “Is the average exposure the same?” - they can ask: “Is the exposure consistent enough across all patient types to be safe and effective?”How PopPK proves equivalence - without a traditional study

PopPK doesn’t just show that two drugs have similar average levels. It shows whether the range of exposure is similar across different patient groups. For example, imagine two versions of a drug used to treat epilepsy. One is the brand, the other a generic. In a traditional study, you’d only test healthy volunteers. But in PopPK, you analyze data from 300 patients: children, seniors, people with liver disease, and those on other seizure meds. You build a model that predicts how each patient’s drug level changes based on their traits. Then you compare the predicted exposure ranges for both drugs. If the 90% confidence interval for the ratio of exposures stays within 80-125% across all subgroups - even in the most vulnerable - you’ve proven equivalence in a way traditional studies never could. The FDA’s 2022 guidance made this official: PopPK data can replace some postmarketing studies if the model is strong and the data are high-quality. In fact, between 2017 and 2021, about 70% of new drug applications included PopPK analyses to support dosing and equivalence claims.

When PopPK shines - and when it doesn’t

PopPK is especially powerful for drugs with a narrow therapeutic index - where small changes in dose or exposure can cause big problems. Think of drugs like digoxin, cyclosporine, or the anticoagulant dabigatran. In these cases, proving consistent exposure across diverse patients is more important than proving identical average levels. It’s also the only realistic way to prove equivalence for biologics - large, complex molecules like insulin or monoclonal antibodies. You can’t give 50 people multiple blood draws over days just to compare a biosimilar to the original. PopPK uses sparse data from real-world use to show exposure profiles are similar. But PopPK isn’t a magic bullet. It struggles with drugs that have extremely high variability in how people absorb them. In those cases, traditional replicate crossover studies still give more precise estimates of within-person variation. Also, PopPK needs good data. If the original clinical trial wasn’t designed with PopPK in mind - sparse sampling, inconsistent timing, missing patient details - the model will be weak. That’s why experts say PopPK planning should start in Phase 1, not as an afterthought.Tools, training, and real-world challenges

Running a PopPK analysis isn’t something you do in Excel. It requires specialized software like NONMEM, Monolix, or Phoenix NLME. NONMEM, developed in the 1980s, is still the industry standard - used in 85% of FDA submissions. Learning to use it properly takes time. Pharmacometricians typically need 18 to 24 months of hands-on training to build models that regulators will accept. And even then, validation is a hurdle. A 2023 survey found that 65% of industry professionals named model validation as their biggest challenge. Why? Because there’s no single agreed-upon way to test if a PopPK model is “right.” Is it good because it fits the data well? Because it predicts outcomes accurately? Because it matches results from other studies? The lack of standardization has led to delays - 30% of PopPK submissions in 2019-2021 got requests for more information from regulators. Still, companies are investing heavily. Nine out of ten of the top 25 pharmaceutical companies now have dedicated pharmacometrics teams, up from two-thirds in 2015. Why? Because PopPK saves money. In cases where it’s successfully used, companies report cutting additional clinical trials by 25-40%.

The future: machine learning and global standards

The field is evolving fast. A January 2025 study in Nature showed how machine learning can detect hidden patterns in PopPK data - like how a combination of low kidney function and a specific drug interaction unexpectedly boosts exposure. Traditional models might miss this. Machine learning spots it. Regulators are catching up. The FDA’s 2022 guidance was a turning point. The EMA and Japan’s PMDA have followed with similar standards. Now, groups like the IQ Consortium are working on global validation frameworks to be finalized by late 2025. This could mean one PopPK model accepted across the U.S., Europe, and Japan - cutting development time and costs worldwide. The direction is clear. As the FDA put it: PopPK “is definitely the direction of travel for pharmacokinetics.” It’s not replacing traditional bioequivalence studies - it’s expanding what equivalence means. No longer is it just about averages. It’s about consistency across real people - with real differences in age, weight, disease, and genetics.What this means for patients and prescribers

For you, the patient, this means safer, more personalized medicine. Generic drugs approved using PopPK aren’t just “similar” - they’ve been shown to behave the same way in people like you. Whether you’re a senior with reduced kidney function or a child taking a liquid formulation, the data backs up the claim that the drug will work as expected. For doctors, it means more confidence in switching between brands and generics, even in complex cases. No more guessing whether a change might throw off a patient’s control. And for the system? It means faster access to affordable drugs without compromising safety. PopPK turns messy, real-world data into a tool for precision - proving that two pills aren’t just chemically identical, but clinically interchangeable.Is population pharmacokinetics the same as traditional bioequivalence testing?

No. Traditional bioequivalence testing compares average drug levels in a small group of healthy volunteers using intensive blood sampling. PopPK uses sparse data from hundreds of real patients - including those with illnesses, different ages, or on other medications - to model how drug exposure varies across the population. It doesn’t just check if averages match; it checks if the full range of exposure is consistent across subgroups.

Can PopPK replace all bioequivalence studies?

Not yet. PopPK is best for drugs with narrow therapeutic windows, complex dosing, or when testing in vulnerable populations isn’t feasible. For drugs with very high variability or simple pharmacokinetics, traditional crossover studies still provide more precise estimates of within-subject variation. Regulators often require both approaches for high-risk drugs.

What software is used for population pharmacokinetics modeling?

The most widely used software is NONMEM, which has been the industry standard since the 1980s and is used in 85% of FDA submissions. Other tools include Monolix, Phoenix NLME, and R packages like nlme and mrgsolve. These require advanced statistical training and are not user-friendly for non-specialists.

Why do some regulators hesitate to accept PopPK for equivalence claims?

Mainly because of inconsistent validation methods. There’s no universal standard for proving a PopPK model is reliable. Some regulators worry about overfitting, lack of transparency in model-building, or insufficient data quality. The FDA is more accepting than some EMA committees, but global harmonization efforts are underway to address these concerns by late 2025.

How many patients are needed for a reliable PopPK analysis?

The FDA recommends at least 40 participants, but the ideal number depends on the drug and the expected variability. For drugs with strong covariates like weight or kidney function, 100-200 patients may be needed. More importantly, the data must be well-distributed across key subgroups - not just a large number of similar patients.

Is PopPK used for biosimilars?

Yes, it’s often essential. Traditional bioequivalence studies don’t work for large biologic molecules like monoclonal antibodies or insulin. Their size and complexity make direct comparisons nearly impossible. PopPK uses sparse clinical data from real patients to show that the biosimilar’s exposure profile matches the reference product across diverse populations - making it the primary method for biosimilar approval.

What’s the biggest mistake companies make when using PopPK?

Waiting too long to plan for it. Many companies collect PK data in Phase 1 without considering PopPK needs - sparse sampling, poor covariate recording, inconsistent timing. This leads to weak models later. The best results come when PopPK is built into study design from the start, not added as an afterthought.

Written by Martha Elena

I'm a pharmaceutical research writer focused on drug safety and pharmacology. I support formulary and pharmacovigilance teams with literature reviews and real‑world evidence analyses. In my off-hours, I write evidence-based articles on medication use, disease management, and dietary supplements. My goal is to turn complex research into clear, practical insights for everyday readers.

All posts: Martha Elena