Generic drugs save patients and the healthcare system billions each year. In the U.S., 90.7% of all prescriptions are filled with generics - but not all generics are created equal. For most medications, switching from brand to generic is seamless and safe. But for some, even small differences in how the drug is made can lead to real harm. Pharmacists are often the last line of defense. Knowing when to pause, question, or flag a generic substitution isn’t just good practice - it’s critical for patient safety.

Not All Generics Are Equal - Here’s Why

The FDA requires generic drugs to have the same active ingredient, strength, dosage form, and route of administration as the brand-name version. They must also prove bioequivalence: meaning the body absorbs the drug at a rate and extent within 80% to 125% of the brand. Sounds strict, right? But that 20% variation window is where problems start. For drugs like levothyroxine, warfarin, or phenytoin - known as narrow therapeutic index (NTI) drugs - even a 10% shift in blood levels can mean the difference between control and crisis. A patient on levothyroxine might go from a stable TSH of 2.1 to 8.7 after switching manufacturers. That’s not a fluke. Studies show NTI drugs have 2.3 times higher rates of therapeutic failure when switched between generic brands. Extended-release formulations are another red zone. A 2020 FDA review found that 7.2% of generic extended-release opioids failed dissolution testing - meaning the drug didn’t release properly over time. Patients didn’t get the steady pain relief they needed. Some got too much too fast. Others got too little. Neither outcome is acceptable.When to Raise the Red Flag

Pharmacists don’t need to wait for a disaster. There are clear, actionable signs that a generic may be problematic:- Patient reports sudden change in effectiveness - especially within 2-4 weeks of switching generics. If someone says, “My blood pressure won’t come down,” or “I’m having seizures again,” don’t assume it’s noncompliance. Check the manufacturer.

- Unexplained side effects - nausea, dizziness, or rash that didn’t happen before the switch. The FDA’s MedWatch database shows 37.6% of patient complaints about generics relate to inconsistent effectiveness, and 28.1% to unexpected side effects after switching manufacturers.

- Therapeutic drug monitoring results are off - if a patient’s blood level of tacrolimus, digoxin, or phenytoin suddenly drops or spikes, and the only change was the generic brand, that’s a red flag.

- Look-alike, sound-alike confusion - oxycodone/acetaminophen and hydrocodone/acetaminophen are frequently mixed up. So are diltiazem CD and diltiazem ER. One letter, one number, one packaging change - and a patient gets the wrong dose.

- Multiple switches in a short time - if a patient’s prescription keeps changing manufacturers every month, that’s a recipe for instability. Especially with NTI drugs.

What the FDA and Experts Say

The FDA insists generics are safe. Dr. Janet Woodcock, former head of the FDA’s drug center, said: “The FDA requires generic drugs to have the same quality, strength, purity, and stability as brand-name drugs.” That’s true - on paper. But Dr. Philip Alcabes, a public health professor, puts it bluntly: “The bioequivalence standard allows for up to 20% variation in drug exposure. For some medications, that’s the difference between life and death.” The American Pharmacists Association (APhA) agrees. Their 2023 guidelines say pharmacists must flag substitutions when patients with NTI drugs report problems. They specifically mention tacrolimus - a drug used after organ transplants - where even minor changes can trigger rejection. The Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP) adds that 14.3% of all generic medication errors come from name confusion. That’s not a rare glitch. It’s systemic. And it’s preventable.

How Pharmacists Can Act - Step by Step

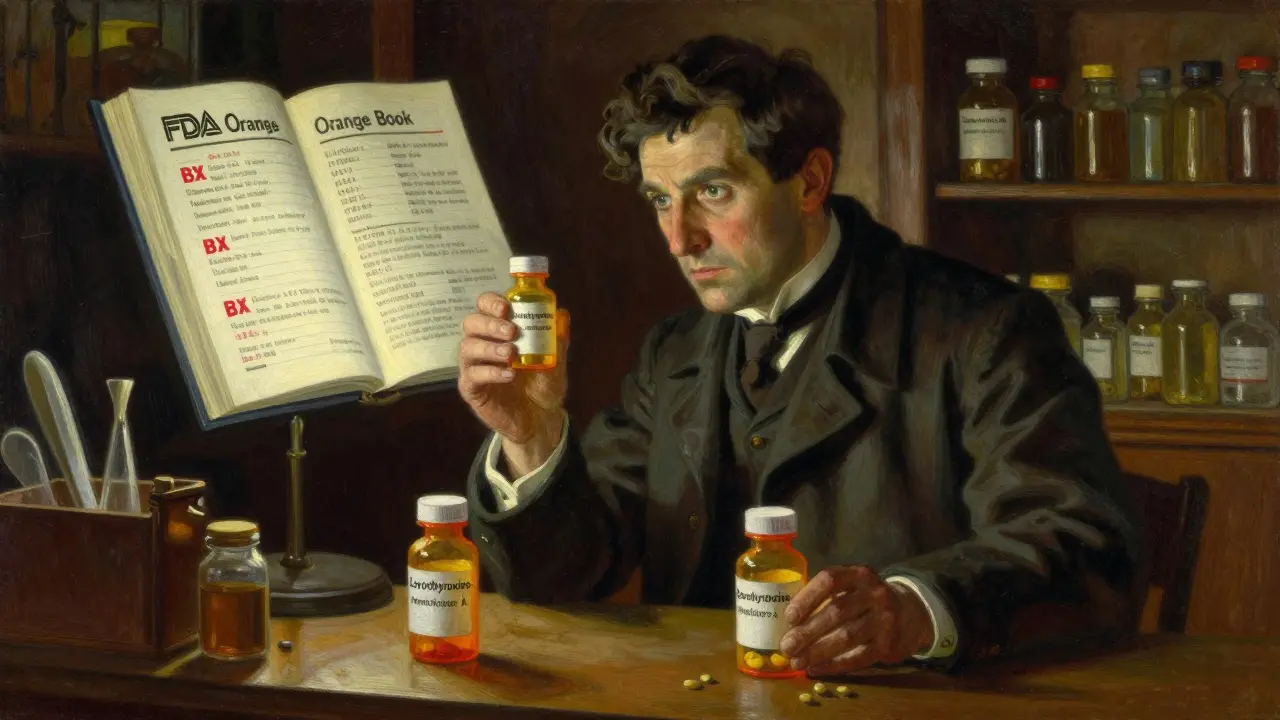

You don’t need to be a scientist to spot trouble. Here’s what to do:- Check the Orange Book - The FDA’s database shows which generics are rated “AB” (therapeutically equivalent) and which are “BX” (not equivalent). If a generic is BX, don’t dispense it without consulting the prescriber.

- Record the manufacturer - Every time you fill a generic, write down the manufacturer name and lot number. If a patient has an issue later, you’ll need that info to trace the problem. Studies show 68.4% of therapeutic failure investigations require manufacturer-specific data.

- Ask the patient - Don’t assume they know what changed. Ask: “Have you noticed anything different since your last refill?” or “Did your doctor change your prescription, or did the pharmacy switch brands?”

- Communicate with the prescriber - If a patient has a problem, call the doctor. Don’t wait. For NTI drugs, many prescribers prefer to specify “dispense as written” or “no substitutions.” Respect that.

- Report it - Use the FDA’s MedWatcher app or ISMP’s reporting system. A pharmacist-reported incident in 2022 led to the FDA issuing a safety alert on certain generic diltiazem CD products after 47 cases of therapeutic failure.

Real Cases That Changed Practice

One patient in Wisconsin switched from one generic levothyroxine to another. Her TSH jumped from 2.1 to 8.7 in six weeks. She was fatigued, gaining weight, and her heart rate dropped. Her pharmacist pulled the old and new bottles. Different manufacturers. Same active ingredient. But different fillers and coating. The pharmacist contacted the doctor. The patient was switched back. Her TSH returned to normal in four weeks. Another case: a man on warfarin was switched to a new generic. His INR climbed from 2.8 to 5.9 - a dangerous level. He nearly bled out. The pharmacist checked the lot number. The manufacturer had changed the tablet’s core formulation without notifying the FDA. That case triggered a nationwide recall. These aren’t outliers. They’re warnings.The Bigger Picture: Cost vs. Safety

Generics save money - that’s their purpose. On average, they cost 80-85% less than brand-name drugs. In 2023, they made up only 23% of total U.S. drug spending despite being used in 90.7% of prescriptions. But pushing for the cheapest generic every time - without regard for formulation, manufacturer, or patient history - puts lives at risk. States with “presumed consent” laws (where pharmacists can substitute unless the doctor says no) have higher substitution rates - but also more reports of issues with NTI drugs. The FDA is responding. Their 2023 Drug Competition Action Plan includes 28 new guidances for complex generics. They’re increasing testing by 40% over the next three years. They’re using AI to detect patterns in adverse event reports. But until those systems are fully in place, pharmacists are the real-time sensors. You see the patient. You hold the bottle. You know what changed.

What You Can Do Today

You don’t need new software. You don’t need a special degree. You just need to pay attention.- When a patient complains about a new generic, don’t brush it off. Document it.

- For NTI drugs, always check the Orange Book. If it’s BX, call the prescriber.

- Keep a log of manufacturers for each patient on critical meds.

- Speak up. If you see a pattern - more than one patient having the same issue with the same generic - report it.

- Ask your state board if you’re required to take generic drug training. If not, take it anyway.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are all generic drugs safe?

Most are. For the vast majority of medications - like statins, antibiotics, or blood pressure pills - generics work just as well as brand names. But for narrow therapeutic index (NTI) drugs like levothyroxine, warfarin, or phenytoin, even small differences in how the drug is absorbed can cause serious problems. The FDA approves generics based on average bioequivalence, but individual patients may react differently.

What does ‘AB’ and ‘BX’ mean in the FDA’s Orange Book?

‘AB’ means the generic is rated as therapeutically equivalent to the brand-name drug. You can substitute it without concern. ‘BX’ means the FDA does not consider it therapeutically equivalent - often because of unresolved bioequivalence issues, inconsistent release profiles, or lack of adequate data. Never dispense a BX-rated generic unless the prescriber specifically orders it.

Can switching between generic brands cause problems even if they’re both AB-rated?

Yes. Even two AB-rated generics from different manufacturers can have different inactive ingredients, coatings, or manufacturing processes that affect how the drug is released or absorbed. This is especially true for extended-release products. A patient stable on one AB-rated brand may have a reaction when switched to another - even if both are technically approved. That’s why documenting the manufacturer matters.

How do I know if a drug is a narrow therapeutic index (NTI) drug?

The FDA has designated 18 drugs as NTIs. Common ones include levothyroxine, warfarin, phenytoin, carbamazepine, cyclosporine, tacrolimus, and digoxin. If you’re unsure, check the FDA’s Orange Book - NTI drugs are often flagged in the therapeutic equivalence section. When in doubt, assume it’s NTI and proceed with caution.

What should I do if a patient says their generic isn’t working?

Don’t dismiss it. Ask when they started the new generic, what symptoms they’re noticing, and whether they’ve switched manufacturers before. Check the Orange Book for the specific product. Look at recent lab values if available. Contact the prescriber with your findings. In many cases, switching back to the original brand or manufacturer resolves the issue. Patient reports are often the first warning sign of a systemic problem.

Written by Martha Elena

I'm a pharmaceutical research writer focused on drug safety and pharmacology. I support formulary and pharmacovigilance teams with literature reviews and real‑world evidence analyses. In my off-hours, I write evidence-based articles on medication use, disease management, and dietary supplements. My goal is to turn complex research into clear, practical insights for everyday readers.

All posts: Martha Elena