For decades, Africa relied on medicine shipped from overseas to fight HIV. When antiretroviral drugs first became available, they cost over $10,000 a year per person. By 2015, Indian generics brought that down to under $100-but even then, nearly 80% of all medicines used across the continent still came from outside Africa. That meant delays, shortages, and vulnerability to global disruptions like the COVID-19 pandemic. But something changed in 2025. For the first time ever, the Global Fund bought an HIV treatment made in Africa.

The First African-Made HIV Treatment Approved for Global Use

On May 6, 2025, a shipment of TLD (tenofovir, lamivudine, dolutegravir) left a factory in Kenya and arrived in Mozambique. It wasn’t just any shipment. This was the first time the Global Fund had ever procured a first-line HIV treatment manufactured on African soil. The drug was produced by Universal Corporation Ltd, a Kenyan company that became the first African manufacturer to receive WHO prequalification for this exact regimen in 2023. WHO prequalification isn’t easy-it means the medicine meets the same strict standards as those from the U.S. FDA or European regulators. And now, this single product can treat over 72,000 people each year.This isn’t a one-off experiment. It’s the start of a continent-wide shift. For too long, African countries had to wait for medicines to arrive from halfway across the world. Now, with local production, treatment can reach remote clinics faster, supply chains are more stable, and prices are starting to drop even further. As Mozambique’s Minister of Health, Dr. Ussene Hilário Isse, said: “Africa’s growing capacity to locally produce lifesaving medications marks a strategic shift for our continent.”

Why TLD Is the New Gold Standard

TLD isn’t just another HIV pill. It’s the current global best practice for first-line treatment. Compared to older regimens, dolutegravir-the key component in TLD-works better, causes fewer side effects, and is much harder for the virus to resist. That’s critical in places where people might miss doses due to distance, stigma, or lack of consistent care. A drug that stays effective even with imperfect adherence saves lives.Before TLD, many African countries were still using older combinations that required more pills, had worse side effects, and were easier for HIV to overcome. The shift to TLD has been slow because of cost and supply issues. But now, with African manufacturers producing it locally, the price is expected to fall even more. That means more people can get on treatment-and stay on it.

From Imports to Innovation: Building African Pharma Capacity

Africa doesn’t just need to make pills-it needs to build the whole system around them. That includes regulatory agencies that can approve drugs quickly, labs that test quality, and supply chains that deliver to rural clinics. Countries like South Africa and Nigeria are leading the way.In Nigeria, Codix Bio is now producing HIV rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs) thanks to a technology transfer deal with SD Biosensor, supported by WHO and the Medicines Patent Pool. This means people can get tested and start treatment in the same day, even in villages without hospitals. In South Africa, the government approved the twice-yearly injectable HIV treatment, cabotegravir long-acting, in record time-just months after it was available in the U.S. Six local manufacturers are already preparing to make generic versions.

The African Union’s Pharmaceutical Manufacturing Plan for Africa (PMPA) aims to raise local production from just 2-3% of the continent’s needs to 40% by 2040. That’s ambitious. But it’s possible-because the market is changing. The Global Fund isn’t just buying drugs; it’s creating predictable demand. That gives African companies the confidence to invest in factories, hire engineers, and train technicians.

How the Global Fund Is Changing the Rules

The Global Fund used to buy almost all its HIV drugs from India. That worked for years. But it didn’t build local resilience. Now, it’s deliberately shifting its procurement strategy. By prioritizing African-made products, it’s sending a clear signal: if you make quality medicine in Africa, we’ll buy it.This is called “market shaping.” It’s not charity-it’s economics. By guaranteeing volume, the Global Fund reduces risk for manufacturers. That lowers prices. And it creates competition. In 2025, the first African-made TLD was priced at 15% below the Indian version. That’s not a fluke. It’s the result of intentional policy.

Mark Edington, Head of Grant Management at the Global Fund, says accelerating African-made health products “will continue to be a top priority.” That’s not just talk. The Global Fund’s next funding cycle (GC7) will include specific targets for African procurement. Countries applying for grants will be asked: How are you supporting local manufacturers?

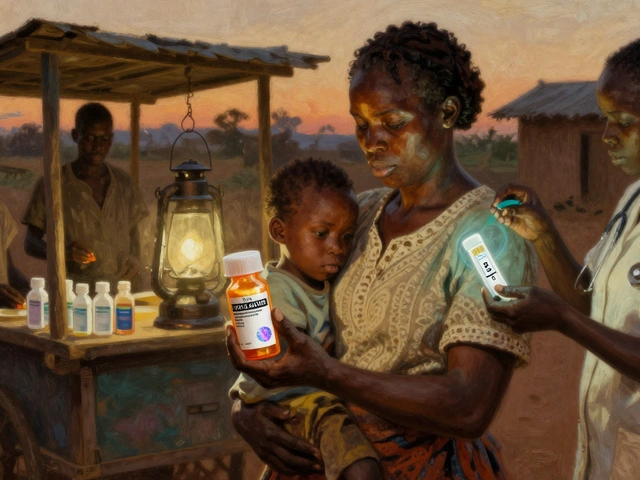

The Next Wave: Long-Acting Injections and PrEP

HIV treatment isn’t just about pills anymore. In October 2025, South Africa became the first African country to register cabotegravir long-acting-a shot given every two months instead of daily pills. It’s a game-changer for people who struggle with adherence or want more privacy.Gilead Sciences, the original maker, has signed licensing deals with six African companies to produce generic versions. Experts predict these generics could cost 80-90% less than the brand-name version. That’s huge. Right now, the injectable costs over $1,000 per dose in high-income countries. If African manufacturers bring it down to $10-$20, millions could access it.

And it’s not just treatment. Prevention is moving forward too. Gilead has partnered with the U.S. State Department and the Global Fund to supply lenacapavir, a new long-acting PrEP drug, at no profit until generics are ready. They plan to submit regulatory applications in 18 high-burden African countries by the end of 2025. That means in 2026, people at high risk of HIV could get a shot every six months instead of a daily pill.

Challenges Still Remain

Progress is real-but it’s not fast enough. Africa needs about 15 million person-years of first-line ARVs every year. Right now, African manufacturers can cover maybe 5-10% of that. Even with new factories coming online by late 2025, scaling up takes time. Regulatory systems vary across countries. Some still lack the staff or funding to review applications quickly.There’s also the issue of funding. While the Global Fund, Unitaid, and the Gates Foundation are investing heavily, African governments need to step up too. Many still spend more on importing medicines than on supporting local production. That’s backwards. Building a pharmaceutical industry isn’t a cost-it’s an investment in health security.

And then there’s the bigger picture: HIV care can’t exist in a silo. Too often, testing, treatment, counseling, and support services operate separately. The 2025 Africa’s Radical Agenda for HIV Sustainability calls for “integration of programme governance.” That means linking HIV programs with maternal health, tuberculosis care, and primary clinics. Only then can we reach the UNAIDS 95-95-95 targets: 95% of people knowing their status, 95% on treatment, and 95% virally suppressed.

Right now, Eastern and Southern Africa are close: 93%-83%-78%. But Western and Central Africa lag behind at 81%-76%-70%. Local manufacturing alone won’t fix that. But it’s a necessary foundation.

What Comes Next?

By 2030, African-made antiretrovirals could supply 20-30% of the continent’s needs. That’s not the end goal-it’s the starting point. The real win isn’t just cheaper pills. It’s control. Control over supply. Control over pricing. Control over innovation.African scientists are now designing drugs tailored to regional strains of HIV. African engineers are building cold-chain systems for long-acting injectables. African regulators are learning to approve medicines faster without sacrificing safety. This isn’t just about HIV. It’s about building a health system that can respond to the next pandemic, the next outbreak, the next crisis.

The story of antiretroviral generics in Africa isn’t about aid anymore. It’s about ownership. And for the first time, Africa is writing its own chapter.

Written by Martha Elena

I'm a pharmaceutical research writer focused on drug safety and pharmacology. I support formulary and pharmacovigilance teams with literature reviews and real‑world evidence analyses. In my off-hours, I write evidence-based articles on medication use, disease management, and dietary supplements. My goal is to turn complex research into clear, practical insights for everyday readers.

All posts: Martha Elena