When a brand-name drug loses patent protection, the race to sell the cheapest version begins. But not all generics are created equal. Two types enter the market: the first generic and the authorized generic. Their timing isn’t just a matter of who gets there first-it changes everything about how much you pay for your medicine.

What Is a First Generic?

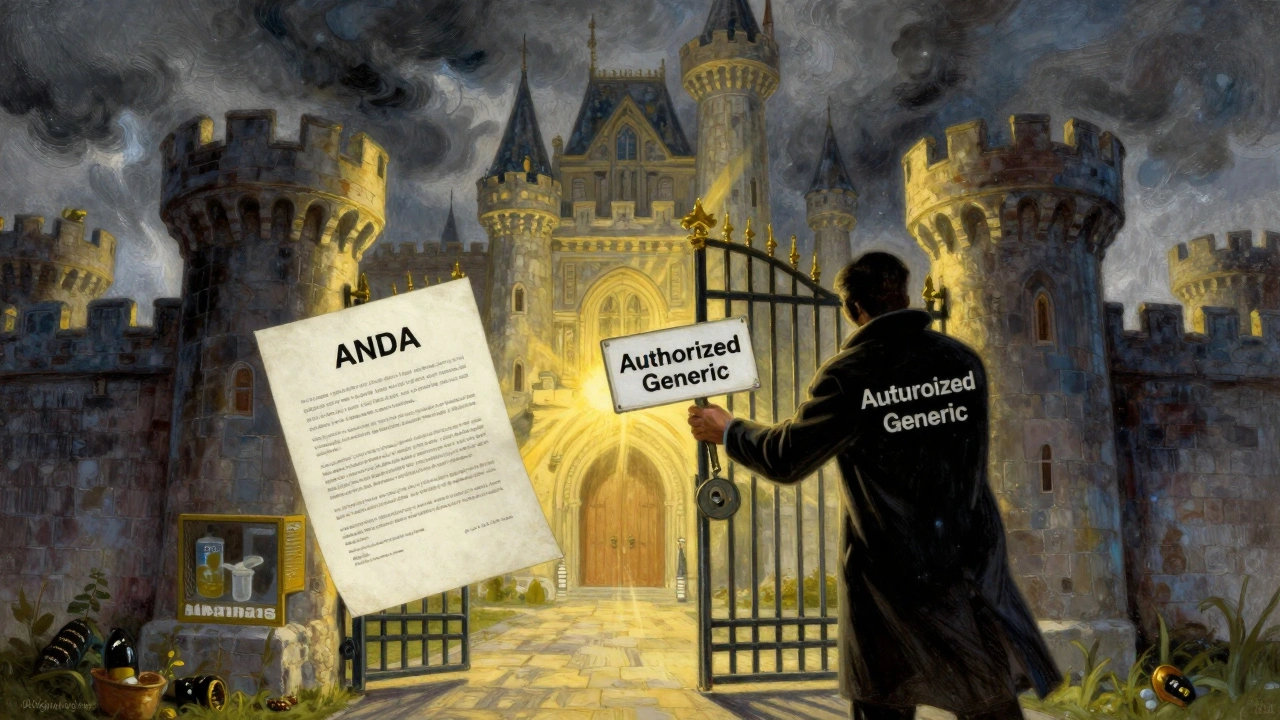

A first generic is the first company to successfully challenge a brand-name drug’s patent and get FDA approval to sell a generic version. This isn’t easy. It takes years of legal battles, clinical testing, and paperwork. Under the Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984, the first company to file an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) gets 180 days of exclusive rights to sell that generic. During that time, no other generic can legally enter the market.This exclusivity isn’t just a reward-it’s the whole reason generic companies risk millions. They invest $5 million to $10 million per drug, often spending years in court fighting patent lawsuits. In return, they expect to capture 70% to 90% of the market. For a blockbuster drug like Lyrica or Lipitor, that could mean hundreds of millions in revenue.

But here’s the catch: that 180-day window is under constant threat.

What Is an Authorized Generic?

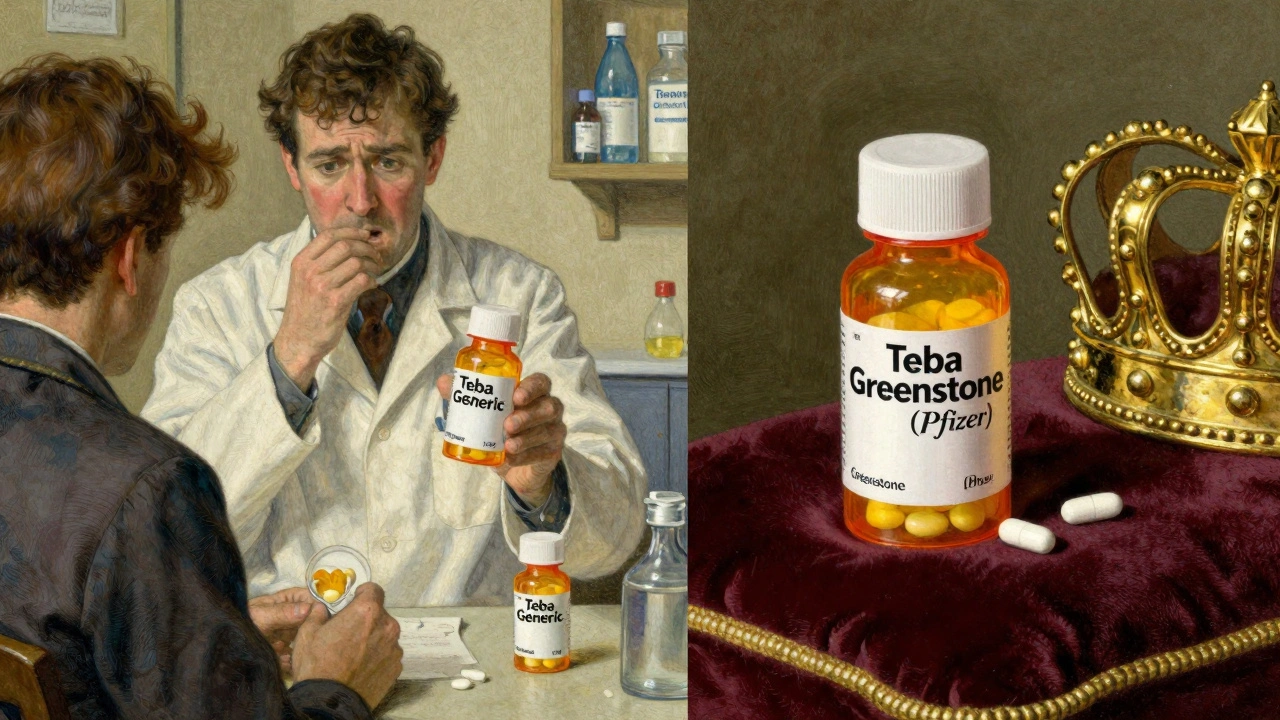

An authorized generic is the brand-name drug itself-same active ingredient, same factory, same pill-but sold under a generic label. It’s made by the original manufacturer or a company they’ve licensed. Unlike traditional generics, it doesn’t need FDA approval through an ANDA. It can launch anytime the brand company decides.That’s the key difference. First generics must wait for the FDA to approve their application. That process can take 10 months to over three years. Authorized generics? They can hit the shelves the same day the first generic launches. No delay. No paperwork. Just a new label and a lower price tag.

Brand companies use this to their advantage. When they see a first generic is about to enter the market, they often roll out their own version immediately. This isn’t an accident. It’s a calculated move.

How Timing Changes the Game

The most important thing to understand is timing. According to research from Health Affairs (2022), 73% of authorized generics launch within 90 days of the first generic. Over 40% launch on the exact same day.Imagine this: Teva launches the first generic for Lyrica in July 2019. Within hours, Pfizer-Lyrica’s original maker-drops its own authorized generic through Greenstone LLC. Suddenly, instead of Teva owning 80% of the market, they’re sharing it with the brand. By the end of the month, Pfizer’s version grabs 30% of sales. Teva’s profits shrink. Patients still pay more than they should.

This is exactly what the Hatch-Waxman Act was meant to prevent. The law was designed to break brand monopolies by giving first generics a head start. But when the brand company itself enters the generic market, it turns the system upside down.

Price drops that should hit 80-90% end up at only 65-75%. That might sound like a big discount-but it’s billions in lost savings for patients and insurers. The RAND Corporation found that this practice costs the U.S. healthcare system billions each year.

Why Authorized Generics Are So Effective

Authorized generics win because they’re not just cheaper-they’re trusted. Patients and pharmacists know the pill is identical to the brand. No questions. No doubts. No switching concerns.Meanwhile, the first generic, even though it’s FDA-approved and bioequivalent, still faces skepticism. Some doctors won’t prescribe it. Some pharmacies won’t stock it. Some patients refuse to take it.

So the brand company doesn’t just compete on price. They compete on trust. And they win.

It’s also faster. While first generics wait for FDA review, authorized generics are already sitting in warehouses. All the brand company needs is permission from the FDA to repackage and relabel. That can happen in days.

Which Drugs Are Most Affected?

This isn’t happening to every drug. It’s targeted. The biggest battles are over high-revenue medications in three areas:- Cardiovascular (32% of cases)

- Central nervous system (24%)

- Metabolic disorders (18%)

Drugs like Eliquis (apixaban), Jardiance (empagliflozin), and Neurontin (gabapentin) are frequent targets. These are pills millions take daily. Profit margins are huge. When generics enter, the brand company doesn’t want to lose control.

Look at Lipitor (atorvastatin). When its patent expired, Pfizer launched its own authorized generic. The first generic maker, Mylan, still made money-but far less than expected. The market share split 50/50. Price drops stalled. Patients paid more for longer.

Who Wins? Who Loses?

The brand companies win. They keep control of the market. They maintain higher prices. They turn a potential threat into a profit stream.The first generic companies lose. They spent years and millions to get there-only to be undercut by the very company they challenged. Many smaller generic manufacturers now avoid patent challenges altogether. Why risk $8 million if the brand can just launch a copy the same day?

Patients lose too. Even though they get a generic, they don’t get the full price drop. Insurers pay more. Medicare pays more. The system pays more.

There’s one exception: sometimes, authorized generics do lower prices faster. The Association for Accessible Medicines argues that when a brand company launches an authorized generic, it pushes the market toward lower prices quicker than if no generic had entered at all. That’s true-but it’s not the same as real competition. It’s the brand playing both sides.

How Is the System Responding?

The government is starting to notice. The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 explicitly says authorized generics don’t count as “generic competitors” when Medicare negotiates drug prices. That’s a big deal. It means the government can treat them like brand drugs for pricing purposes-opening the door to lower negotiated rates.The FTC has also taken action. In the 2013 FTC v. Actavis case, the Supreme Court ruled that “pay-for-delay” deals-where brand companies pay generics to delay entry-are illegal. Some of those deals involved coordinated authorized generic launches. But enforcement is still patchy. Most cases never go to court.

Meanwhile, the FDA approved 80 first generics in 2017-but only about 10% of generic applications get approved on the first try. The rest sit in review limbo for years. That backlog gives brand companies more time to plan their authorized generic strikes.

What’s Next for Generic Drug Entry?

The game is changing. Generic companies are adapting. Some are building dual strategies: they file ANDAs, but also partner with brand manufacturers to get early access to authorized generics. Others are focusing on drugs with fewer competitors, where the 180-day window still has value.By 2027, analysts at Evaluate Pharma predict authorized generics will make up 25-30% of all generic prescriptions-up from 18% in 2022. That means more patients will get a generic version of their drug-but it might still be made by the same company that sold them the brand version.

The real question isn’t whether you get a generic. It’s whether you get the lowest possible price. And right now, the system is rigged to make sure you don’t.

What You Can Do

As a patient, you can’t control when a generic enters the market. But you can ask questions:- Is this the first generic, or is it an authorized generic?

- Why is the price still high even though it’s generic?

- Can I switch to a different generic if this one is too expensive?

Pharmacists can help. Some can tell you if your drug is an authorized generic. If your copay is still $50 for a drug that should cost $5, it’s worth asking why.

And if you’re on Medicare or have a private plan, check your formulary. Some insurers are starting to exclude authorized generics from preferred tiers because they don’t deliver the savings they should.

The system was built to save money. But the rules have been bent. The first generic was meant to be the hero. Instead, it’s often the first casualty.

What’s the difference between a first generic and an authorized generic?

A first generic is the first company to get FDA approval to sell a generic version of a brand-name drug after challenging its patent. It gets 180 days of exclusivity. An authorized generic is made by the brand company or a licensed partner, sold under a generic label, and doesn’t need FDA approval-it can launch anytime, even during the first generic’s exclusivity period.

Why do authorized generics hurt first generic companies?

They enter the market at the same time or right after the first generic, splitting the customer base. Instead of capturing 80-90% of the market, the first generic might end up with only 45-60%. That cuts their revenue dramatically, making their years of legal and regulatory investment less profitable-or even a loss.

Do authorized generics lower drug prices?

They lower prices compared to the brand-name drug, but not as much as true generic competition. When an authorized generic enters, prices drop only 65-75% instead of the 80-90% seen when multiple independent generics compete. That means patients and insurers pay more than they should.

Are authorized generics safer or better than first generics?

No. Both are FDA-approved and bioequivalent. Authorized generics are often made in the same factory as the brand-name drug, so they’re identical. First generics are also identical in active ingredients. The difference is in who makes them and when they enter the market-not in quality or safety.

Can I avoid authorized generics to get a lower price?

Sometimes. If your pharmacy stocks multiple generics, ask for one that’s not labeled as an authorized generic. Independent generics-made by companies like Teva, Mylan, or Sandoz-are more likely to be priced lower because they’re competing against each other, not the brand.

Why does the FDA allow authorized generics?

The FDA doesn’t regulate the marketing strategy of drug companies. As long as the product is safe, effective, and properly labeled, it can be sold. Authorized generics are legal because they don’t violate any safety or approval rules-they just exploit a loophole in the competitive system created by the Hatch-Waxman Act.

What’s being done to fix this problem?

The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 excluded authorized generics from Medicare price negotiation rules, treating them more like brand drugs. This could pressure manufacturers to lower prices. The FTC also investigates pay-for-delay deals linked to authorized generics. But enforcement is slow, and the system still favors brand companies.

Written by Martha Elena

I'm a pharmaceutical research writer focused on drug safety and pharmacology. I support formulary and pharmacovigilance teams with literature reviews and real‑world evidence analyses. In my off-hours, I write evidence-based articles on medication use, disease management, and dietary supplements. My goal is to turn complex research into clear, practical insights for everyday readers.

All posts: Martha Elena